I was a country boy, born in the country and raised up in the country. Amazingly, country life changed very little throughout the past hundreds of years. It was harsh. People had to work very hard all year long and could barely make a living. They worked mainly on four areas: rice field, mountain, vegetable garden, and waterfront.

Rice Field

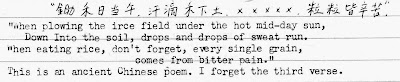

Rice is the main crop in the southern half of China. People spent most of their time in the rice field. Seeding began in early February. The rice grain chosen for seeds was soaked in water daily for budding. The budding seeds were then scattered by hand onto a prepared corner of the rice paddy. In about thirty days, the seeds would grow into green fluffy young rice plants called "yiang". The yiang was then shaved off as sod. The sod was planted into the prepared rice field by hand, in small bundles, one by one, in orderly rows, about one foot apart. Planting was a back-breaking job.

To prepare the rice field, the soil was first tilled over with an ox-powered plow. This was the heaviest job among all farm works. Water was then brought in to flood the field. Water irrigation was so essential in agriculture that it demands all the ingenuity and tedious hard work. Next the tilled and flooded soil was broken loose with an ox-powered rake. Finally all exposed hay stumps and weeds were stepped down by bare feet, to bury them deep into the mud. The field was thus ready for planting.

After planting, again water is vital. Proper water level must be maintained at all times. In heavy rain, the peasants had to patrol the rice field in order to make sure that the yiang was not being drowned by over-flooding, day and night, facing the storm, hurricane or any weather. In dry weather, water must be brought in from the river, ponds or swamps, through the small canals, ditches, or high banks. Then de-weed. Then fertilizer. In about 120 days, the yiang would grow into tall and golden matured rice stalk call "wo", drooping down with heavily laden rice grain. It was ready for harvest. Water was then drained out to let the grain dry.

In harvest, each bundle was cut with a sickle about 6 inches above ground. The grain was then threshed off from the stalks either on the field or at home. On the field, the stalks were threshed against a huge wooden drum. At home (carried home on shoulder), the stalks were threshed against a large smooth-surfaced rock called "wo rock". The empty stalks now become hay. The rice grain must be sun-dried within the next few days, otherwise it would bud and become rotten. The grain was then ready for storage, market or consumption.

For consumption, the lighter grain shell was first ground off by a grain grinder, then blown away from the much heavier rice by a wind-chest or the natural wind. Next the light brown rice membrane was polished off by a rice polisher. The end product, snowy white rice, was then ready for storage, market or cooking. The freshly harvested rice was most delicious.

Hay was utilized to braid ropes, sandals, to feed oxen, or as bedding material for human, ox, pig, or as cooking fuel. Grain shell was utilized as insulator or cooking fuel. Rice membrane was used to feed ox, pig, chicken or human. All ash was utilized as fertilizer. The recycling process was thorough in China. All materials were in such short supply that we Chinese never could afford to waste anything.

All farm work was done in bare feet and with bare hands. Those who could not afford an ox had to plow the rice field with a garden hoe, by hand, one chop at a time, and had to rake the soil with a hand rake, by hand, one piece of soil at a time. That was the way Chinese farmed their land over 3,000 years before the plow was invented and the oxen were harnessed. The plow and oxen revolutionized agriculture, tremendously increasing land productivity and placing Chinese civilization on top of the world.

We owned about three quarters of an acre rice paddy, inherited from great grandfather. In my father's time, my grandmother was a widow and did not farm. After my father left home for America, and all three of us kids grew up a little, mother farmed that land for several years. We hired someone to do the plowing and the raking. Mother did most of the rest. My brother and I helped out in some minor chores. Stomping down the hay stumps into the mud was one of our favorites, in spite of the threat of leeches. Operating the "water wagon" was another chore that we could help mom with. To push the revolving wheel, mom pushed one handle, one of us pushed the other. On the field, kids could do very little else. At home, kids could do more. We helped to sun dry the grain an hay, grain grinding, rice polishing, braiding ropes, picking up manure (with bamboo basket and long bamboo fork).

My brother in particular worked hard. He had a remarkable enduring power to stay up late without sleep. He was the "man of the house," helping mom on almost every house chore, including babysitting my sister and caring for all the domestic animals. That was one reason that he never did have free time to learn swimming as well as I did. At meal time, we never had a dull moment. Mom and my brother always discussed this and that. We were taught the sense of responsibility and decency early in our life. When my brother left home for boarding school, that responsibility fell on me. When I left home for school, it fell on my sister. All three of us were fortunate and smart enough to become an intellectual, and yet not ashamed to do manual labor. We learned cooking, laundry, house cleaning, carrying water from the river, gardening, etc. before we were 10 years old.

Among the farm tools, the most fascinating one was the "water wagon." Ever since I was a little kid, it caught my curiosity. When I was helping mom, I kept watching and analyzing how it worked. I soon "discovered" its mechanism was quite simple. It was nothing but a long wooden cylinder, divided into an upper tunnel and a lower tunnel. Inside the tunnel, an "army" of rectangular boards revolved downward in the upper tunnel, and upward in the lower tunnel. When the little boards returned in the lower tunnel, it caught the water in between two boards, and brought it all the way to the upper end, and emptied it. The trick was the two turning wheels, one at each end, that kept the little boards revolving. Another trick was the hinge joints connecting the boards. The joints could be straightened, and could be bent.

Another fascinating tool was the grain grinder. When I was helping mom, I wondered how it worked. Why the grain kept on coming out and not staying in? Then one time I had the opportunity watching the whole grinder being built from scratch. The trick was the arrangement of the bamboo teeth. They were arranged in a certain angle, so when the upper teeth of the grinder revolved clockwise, all the grain was pushed outward; counter-clockwise, it regurgitated back upward.

The trick of constructing a wooden water bucket was also on the "angle." Many pieces of wooden boards, 2 inches wide and 2 feet long, were cut at a certain slightly slanting angle along each side. When the "sides" were put together, it therefore formed a circular cylinder. They were put together with bamboo nails, both ends of which were sharp and pointy. An old Chinese proverb said: "There was no nail in the world that could have both ends sharp." That means you cannot have things both ways. When there is advantage, there is always some disadvantages. A needle has one sharp end. The other end got to be blunt. But those bamboo nails for water bucket were an exception.

The rice polisher was a permanent fixture in every single household. It remains the same size, same shape and at the same site. It was operated by feet. When the shorter end was forcibly stepped upon, the upper end jumped up, then fell back down into the rice. Each move created a rhythmic sound. When I was helping mom or doing it together with my brother, such rhythmic music amused me. An adult could tilt it alone. Kids like my brother and I were not strong enough to do that. In wealthy families, such work was done by slaves. During the Han Dynasty, the first emperor Liu Bang had many concubines. He particularly favored a young one call Chi (Qi). His empress Looi (Lu) was jealous. At Liu Bang's death, Empress Looi took control of the dynasty and took revenge against concubine Chi. Chi was punished to polish rice, day and night, as a slave. At the time, Chi had a young son, who became a king and was exiled far away to a frontier state. Hearing that rhythmic music, Chi composed and sang a song:

Empress Looi learned about this song and tortured Chi to death. Looi later died of probable breast cancer. That was about 195 B.C. The same rice polisher was still being used in the 20th century.

The "wind chest" was not very common. Most people made good use of the natural wind to blow off the grain shell. At the village square, flying grain shell and debris were all over the place during harvest season. Many particles got into the eyes. I was surprised that no corneal injury or blindness occurred in our village.

In south China, we harvested two rice crops per year. In winter, the rice paddies were either left idle, or transformed into temporary vegetable gardens. Red rice was raised by a few peasants as a side crop. They were just seeded along the river band and left to grow wild. Red rice was used as animal fee, human food, and to brew wine. It was actually a liquor, not wine, very strong and delicious.

Most peasants were not landowners. After paying rent and tax, there was not much left. Lucky ones had two full rice meals a day. Many could only have one full rice and one rice porridge.

No comments:

Post a Comment